David Weigel resigns from the Washington Post for his unprofessional behavior, making an apology on the way out.

I’m a member of an off-the-record list-serv called “Journolist,” founded by my colleague Ezra Klein. Last Monday, I was deluged with angry e-mail after posting a story about Rep. Bob Etheridge (D-N.C.) that was linked by the Drudge Report with a headline intimating that I defended his roughing-up of a young man with a camera; after this, the Washington Examiner posted a gossip item about my dancing at a friend’s wedding. Unwisely, I lashed out to Journolist, which I’ve come to view as a place to talk bluntly to friends.

The WaPo ombudsman explains that Weigel, “bears responsibility for sarcastic and scornful comments he made,” on Journolist, which he describes as “supposedly private” and that this raises questions about the role of Serious bloggers.

With bloggers such as Weigel, “I think The Post needs to decide what it wants to be online,” said Dan Gainor, a vice president at the conservative Media Research Center. “Does it want to be opinion? Or, does it want to be news? The problem here was that it was never clear.”

“If it’s going to be opinion, it ought to have somebody on the conservative side — something Dave Weigel never was,” he said.

If The Post wants to assign a “good neutral reporter” to cover conservatives, “we’d be thrilled,” said Gainor. But quickly added, Weigel “wasn’t one. He looked at the conservative movement as if he was visiting a zoo. We’re more than that.”

Gainor raises valid points. Klein’s blog posts clearly pass through a liberal prism. For that reason, liberals have a comfort level with what he writes, and conservatives know where he’s coming from, even if they disagree. In contrast, Weigel’s blog seemed to confuse many conservatives who contacted me. Was he supposed to be a neutral reporter, some wondered? Others complained that he was a liberal trying to write about conservatives he disdained.

Which brings me to the Serious “liberal” Ezra Klein, who made some very revealing comments on this and what he sees as related.

I was on all sorts of e-mail lists, but none that quite got at the daily work of my job: Following policy and political trends in both the expert community and the media. But I always knew how much I was missing. There were only so many phone calls I could make in a day. There were only so many times when I knew the right question to ask. By not thinking of the right person to interview, or not asking the right question when I got them on the phone, or not intuiting that an economist would have a terrific take on the election, I was leaving insights on the table.

That was the theory behind Journolist: An insulated space where the lure of a smart, ongoing conversation would encourage journalists, policy experts and assorted other observers to share their insights with one another.

Suddenly, he brings in the Rolling Stone profile that got McChrystal fired and reporting on Afghanistan generally.

In a column about Stanley McChrystal today, David Brooks talks about the union of electronic text, unheralded transparency, 24/7 media and a culture that has not yet settled on new rules for what is, and isn’t, private, and what is, and isn’t, newsworthy. “The exposure ethos, with its relentless emphasis on destroying privacy and exposing impurities, has chased good people from public life, undermined public faith in institutions and elevated the trivial over the important,” he writes.

….

Broadly speaking, neither journalism nor the public has quite decided on how to handle this explosion of information about people we’re interested in. A newspaper reporter opposing the Afghanistan war in a news story is doing something improper. A newspaper reporter telling his wife he opposes the war is being perfectly proper. If someone had been surreptitiously taping that reporter’s conversations with his wife, there’d be no doubt that was a violation of privacy, and the gathered remarks and observations were illegitimate. If a batch of that reporter’s e-mails were obtained and forwarded along? People are less sure what to do about it. So, for now, they use it.

So is he implying that being critical of the war in Afghanistan is grounds for being fired? This is pretty interesting because the public is split over Afghanistan:

You would think that a roughly even split would merit commentary “opposing the Afghanistan war” occasionally, especially through the “liberal prism” (a majority of Democrats oppose the war), but no, it’s the job of Serious People to determine the range of acceptable opinion. If they were serious (as opposed to Serious) about reporting, they might raise some of the following points:

First, this argument tends to lump the various groups we are contending with together, and it suggests that all of them are equally committed to attacking the United States. In fact, most of the people we are fighting in Afghanistan aren’t dedicated jihadis seeking to overthrow Arab monarchies, establish a Muslim caliphate, or mount attacks on U.S. soil. Their agenda is focused on local affairs, such as what they regard as the political disempowerment of Pashtuns and illegitimate foreign interference in their country. Moreover, the Taliban itself is more of a loose coalition of different groups than a tightly unified and hierarchical organization, which is why some experts believe we ought to be doing more to divide the movement and “flip” the moderate elements to our side. Unfortunately, the “safe haven” argument wrongly suggests that the Taliban care as much about attacking America as bin Laden does.

Second, while it is true that Mullah Omar gave Osama bin Laden a sanctuary both before and after 9/11, it is by no means clear that they would give him free rein to attack the United States again. Protecting al Qaeda back in 2001 brought no end of trouble to Mullah Omar and his associates, and if they were lucky enough to regain power, it is hard to believe they would give us a reason to come back in force.

Third, it is hardly obvious that Afghan territory provides an ideal “safe haven” for mounting attacks on the United States. The 9/11 plot was organized out of Hamburg, not Kabul or Kandahar, but nobody is proposing that we send troops to Germany to make sure there aren’t “safe havens” operating there. In fact, if al Qaeda has to hide out somewhere, I’d rather they were in a remote, impoverished, land-locked and isolated area from which it is hard to do almost anything. The “bases” or “training camps” they could organize in Pakistan or Afghanistan might be useful for organizing a Mumbai-style attack, but they would not be particularly valuable if you were trying to do a replay of 9/11 (not many flight schools there), or if you were trying to build a weapon of mass destruction. And in a post-9/11 environment, it wouldn’t be easy for a group of al Qaeda operatives bent on a Mumbia-style operation get all the way to the United States. One cannot rule this sort of thing out, of course, but does that unlikely danger justify an open-ended commitment that is going to cost us more than $60 billion next year?

Fourth, in the unlikely event that a new Taliban government did give al Qaeda carte blanche to prepare attacks on the United States or its allies, the United States isn’t going to sit around and allow them to go about their business undisturbed. The Clinton administration wasn’t sure it was a good idea to go after al Qaeda’s training camps back in the 1990s (though they eventually did, albeit somewhat half-heartedly), but that was before 9/11. We know more now and the U.S. government is hardly going to be bashful about attacking such camps in the future. (Remember: we are already doing that in Pakistan, with the tacit approval of the Pakistani government). Put differently, having a Taliban government in Kabul would hardly make Afghanistan a “safe haven” today or in the future, because the United States has lots of weapons it can use against al Qaeda that don’t require a large U.S. military presence on the ground.

Fifth, as well-informed critics have already observed, the primary motivation for extremist organizations like the Taliban and Al Qaeda is their opposition to what they regard as unwarranted outside interference in their own societies. Increasing the U.S. military presence and engaging in various forms of social engineering is as likely to reinforce such motivations as it is to eliminate them. Obama is hoping that a different strategy will eventually undercut support for the Taliban and strengthen the central government, but it is still an open question whether more American involvement will have positive or negative effects. If we are in fact making things worse, then we may be encouraging precisely the outcome we are trying to avoid.

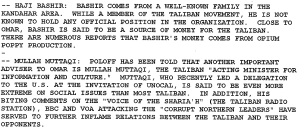

The humanitarian purpose? The State Department was alright with the situation in the 90’s. From a 1997 State Department cable:

But it’s the guy that reports on tea partiers that gets fired for a lack of objectivity.

Good thing the journalist they hired to look into Progressive issues so they would be balanced with the Teabagger journalists is still there…oh, wait, they didn’t hire anyone to look at Progressives…

Also the Big Hollywood guy is offering $100,000 to get a look at the Journolist emails.