I need to begin with a little preface on this about “technical” issues: DON’T PANIC. This is written assuming no prior knowledge, but if you’d like to read up a bit Mike Konczal (a former financial engineer) has compiled a fantastic primer on the technical issues, including interviews with some of the most qualified experts in the country. Dean Baker provides a good summary of our dilemma:

Wall Street is know around the world as the land of the million dollar babies since is chock full of people who have gotten incredibly rich as a result of handouts from the government. These handouts come in all forms, but most in the size extra large. The basic story is always the same; the banks and financial firms take gambles that provide big payoffs for their shareholders and “top performers” and pass along big risks to the taxpayers.

….

We had some hopes of reining in the million dollar babies with the financial reform package, but those hopes appear to be dimming. The effort to downsize the “too big to fail” banks got trounced in the senate last week, garnering just 33 votes. Apparently, the prospect of having to head out into the markets unprotected by the implicit guarantee of government bailouts was too frightening for JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs and the other big banks. Their lobbyists twisted the arms and got the overwhelming majority of the senate to continue the big bank subsidy of free government insurance indefinitely.

Financial reform can more or less be summed up as getting these folks off of their unsustainable welfare program. The rest is a matter of working out details and the media shamelessly taking the sides of the banks out of (somewhat legitimate) concern that offending them too badly might hurt their stock prices.

Just after I’d compiled the following, I saw that Yves Smith (likely among countless others) had also noticed this partiality:

The defenders of the economic orthodoxy have gotten much more shrill of late. In a perverse way, this is probably a positive sign: they might be feeling a tad worried that they are starting to lose their hold over consensus reality. But given how quick various media outlets are to pick up and amplify their messages, it would be more than a tad premature to say that the prevailing belief system is threatened.

It may be sample bias, but I’ve noticed two patterns. The first is a sharp uptick in criticism of “populism†or better yet, “populist angerâ€, which then serves as the basis for arguing that efforts to rein in the financial services industry are overdone. Now usually there is a wrapper around it, like “mistakes were made†or another not-very-convincing bit of crowd pleasing pablum to acknowledge that maybe some change might be warranted, but nothing approaching what those enraged savages want.

….

The finger-shaking at supposed children is overbearing and authoritarian, and amounts to a blanket refusal to deal with the substance of the bill of particulars against the financial services industry. But the part of his formula that is more revealing is his argument that the interests of Wall Street and “the economy†are aligned, and everyone needs to shut up and get with the program, since hurting the economy will be very bad for them.But this is bogus. The economy we now have has increasingly shunted the benefits of production to the top 1%. In the 1960s, it was accepted that increases in productivity would be shared between corporations and workers. No more. We’ve seen a persistent gap rise between wage growth and productivity growth, so the gains in employee output have been siphoned off to the managerial elite and investors.

So these populists, despite the hectoring, aren’t stupid or emotional. Quite the reverse. They’ve been snookered by the system one time too many, and have had enough. Primates as well as people are willing to take losses to punish cheaters, and this is deeply rooted, instinctive behavior for a good reason: you need some measure of fairness for societies to function.

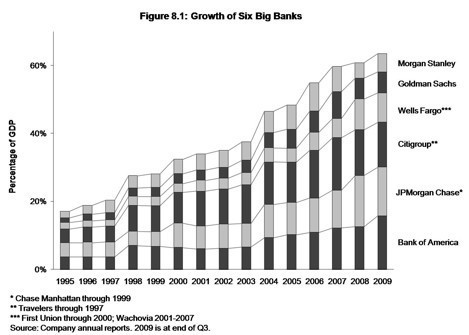

Her claims in visual form:

Source

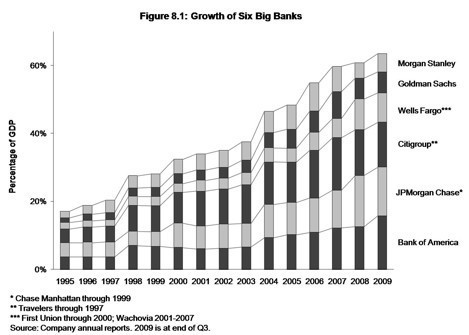

Source

And the nail in the coffin for the use of populist as an epithet here:

The medium financial players are the natural check on the power of the biggest financial players.

I saw something a while back that made me pause. Wall Street Journal, Proxy Plan Roils Talks on Finance Rules:

But in the bill launched this week by Senate Democrats, a little-noticed provision designed to give shareholders more clout is emerging as a stumbling block….The move encountered resistance from business groups…now, the Chamber is mobilizing forces to lobby lawmakers to kill the provision…Kurt Schacht, managing director at CFA Institute, an association for investment professionals that supports the idea, said, “The important test for lawmakers will be whether they can hold the line for these important investor protections. We expect that banking and other special interests will do their level best to strip many of these important protections from the final bill.â€

My first instinct was “Why are the financial lobbyists fighting with the CFA Institute? Aren’t they all on the same team?â€

Do you know what a CFA is? It stands for “Certified Chartered Financial Analyst.†According to here the median compensation for a CFA is $180,000, and CFAs with 10 years of experience or more have reported median compensation of $248,000. At a salary (assuming that’s the household income) around $250,000 this puts them right around the top 1.5% of Americans, with 98.5% of Americans earning below them.

However we’ve just come from an era where all the real earnings growth has gone to the top 1%. So this got me thinking: why is the CFA fighting with the Chamber of Commerce? Don’t their interests line up well? And then it hit me – Chamber of Commerce, the Financial Services Roundtable, the fsforum, they are all representing interests that clock in a notch above the top 1.5%. They are gunning to represent the interests of the top 1% in this current financial reform debate. And the CFAs could lose these fights.

So the only sources of opposition to this are the very top of the financial world, the friends they buy in congress, the corporate media, and executives at blue chip companies who rely on large financial institutions for their unjustifiable compensation. Crying about being persecuted here takes some serious nerve. Still, they’ve proven themselves up to the task.

General Electric’s CEO feels their pain:

In a wide-ranging discussion with Norm Pearlstine, chairman of Bloomberg Businessweek, Immelt spoke about the economy, regulation, the environment and even his own compensation.

“Going a couple years without a bonus isn’t that big of a deal,” Immelt said, joking that he can live on $3 million a year.

….

Immelt also voiced his support for Goldman Sachs Group Inc (GS.N), which has been under scrutiny since the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission charged it with fraud last month.

Immelt said GE is a longtime partner of Goldman’s.

“We trust them,” Immelt said.” “They’ve done great work for us.”

Immelt cautioned that the populist anger at Wall Street is not good for the U.S. economy.

“This is really a moment of time when the world needs the U.S. to be a beacon of stability, a beacon of reliability,” Immelt said.

“People need to tone down the rhetoric around financial services and stop the populism and be adults.”

Apparently “liberal” now means being to the left of billionaires:

Liberal Democrats in the Senate, emboldened by a wave of populism, are trying to make financial regulatory legislation far tougher on Wall Street, potentially restricting or breaking up the biggest banks and financial companies, David M. Herszenhorn reports in The New York Times.

Normally such efforts might attract little concern among Senate leaders or the White House. But the confluence of a high-stakes election year and a pervasive anti-Wall Street sentiment after the recession has given liberals unusual muscle in the debate. It has also raised the prospect that they could succeed in reshaping the bill.

The liberal amendment that could be hardest to defeat — and is among the most deeply dreaded by Wall Street — also has some of the purest populist appeal: a proposal by Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Senator Ted Kaufman of Delaware to break up the nation’s biggest banks by imposing caps on the deposits they can hold and limits on other liabilities.

“Look at what we did to AT&T, look at Standard Oil, basically what you do is you just split it apart,†Mr. Kaufman said in an interview. “If we don’t do that, we have got too big to fail, because when you look at these big complex entities, you cannot resolve them in a major financial crisis.â€

So, according to the New York Times, none of this is being put forward because it’s a good idea, it’s all just shameless opportunism against innocent bystanders, persecution resulting from misdirected blame, and above all, terribly unfair. In fact, it’s comparable to racism:

Politics, some believe, is the organization of hatreds. The people who try to divide society on the basis of ethnicity we call racists. The people who try to divide it on the basis of religion we call sectarians. The people who try to divide it on the basis of social class we call either populists or elitists.

But I’ve saved the best for last because “enraged savages” was anything but hyperbole.

Byron L. Dorgan was viewed as something of a Cassandra last fall, when he started warning fellow Democrats they were in for a 2010 drubbing unless they started talking more about issues that average voters care about — and in ways those voters understand.

But the senator from North Dakota has kept at it. Even after deciding against running for re-election himself, he’s been using his position as chairman of a leadership advisory group, the Democratic Policy Committee, to promote his views as parting advice to his colleagues.

And so it came to be that Drew Westen, a professor of clinical psychology at Emory University, flew from Atlanta to Washington early this spring. He explained to a caucus of Democratic senators, as Dorgan’s guest, his view that the most effective way to win over voters is to use simple language that engages the “frontal emotion circuits†of the brain.

Westen came to the Capitol wearing a pin-striped suit of the sort favored by senators, but his message made clear he wasn’t a member of their club. The senators say he delivered what amounted to an indictment of the party’s efforts to market itself in a time of economic anxiety. The Democratic Party was squandering its control of Washington, he said, by failing to telegraph its achievements and by pressing its agenda too timidly.

As a result, Westen warned, Republicans have been able to capitalize on the burgeoning power of the tea party movement and galvanize an electorate with shrinking confidence that the powers in Washington can create jobs, reduce the deficit or address other domestic challenges.

To revive their flagging prospects for the midterm election, Westen advised that March afternoon, Democrats ought to start by pushing to tighten the regulatory reins on Wall Street — an effort that should have started a year earlier, he said, right after enactment of the $787 billion economic stimulus package.

Many senators gave the psychologist a round of applause. But more important, they have started taking his advice, while also listening to a group of better-known Democratic operatives who have been saying much the same thing. And so, for the six months until Election Day, the party is putting a decidedly populist cast on its congressional agenda and campaign message. “They realized,†Westen says of the party leadership, “the importance of speaking with a clear voice to the anger of the average American.â€